An appellation investigation.

On May 21st of 2024, Ranger Suárez stepped onto the mound to face not his namesake, but his name-mates. He struck out ten Texas Rangers on his way to victory, proving that those born into the name possess greater mettle than those who merely adopt it. There are a few team-player combos that can produce that sort of fun with nomenclature. Some Rays might meet up with the team from Tampa. A guy named Jay might duel his blue counterparts from Toronto. A Redman or a Redmond might find himself playing for, or against, Cincinnatti’s Redlegs. This train of thought produces a question that, while thoroughly unimportant, might produce at least a little curiosity for your Sunday morning. Who is the greatest Phil to play for the Phillies?

It all began on July 11th, 1891, with a road matchup against the National League’s Pittsburgh club (not yet going by the their piratical nickname). The ballgame was not a glorious affair for the Fightin’ Phillies, who were “just too easy for the Pittsburgs to-day”, per the Philadelphia Inquirer. 1 They lost 11-0. But in the 7th inning, a rather momentous pitching change was made, though it is doubtful that anybody thought about it much at the time (or since). Manager Harry Wright tapped young Phil Saylor, a lefty pitcher out of Ohio, to take the mound, and in doing so produced the first ever Phil to play for the Phillies (at least, the first for which we have records). Given Wright’s enormous role in establishing professional baseball, this did not really rank as one of his more memorable contributions to the sport. Saylor finished the game, allowing two earned runs on two hits (one a round-tripper), with no strikeouts or walks.

A few weeks later, the Weekly Kansas Chief newspaper boasted “Phil Saylor, of West Alexandria, Ohio, the son of an old schoolmate of ours, has developed into a famous base ball pitcher, and has been employed by the Philadelphia club. You can’t keep old Preble County down.” 2 But news in those days traveled slowly. By the time the pal of Saylor’s father was crowing in Kansas, the young hurler’s major league career was already over. He never played in another game with the Phillies, or any other big league club. Saylor would return to Ohio, play a single recorded game with the Ohio-Michigan League’s Akron Summits (a complete game-win), and become a well-regarded lawyer. 3

So Saylor was the pioneer Phil, but he was certainly not the greatest.

The next Phil would fare a little better. Phil Geier, hailing from the nation’s capital, made his major league debut with the Phillies in 1896. He stuck around for parts of two seasons, playing the outfield, hot corner and keystone. He slashed .278/.392/.320 in 1897, then departed the City of Brotherly Love and major league baseball. Three years later, he’d return to the National League as a Red, and played for a few more clubs before his career was done.

That’s closer to the mark, but still a far cry from the Great Phil we’re looking for.

In the years following the careers of those two trailblazers, a number of Phils played for Philadelphia’s representative in the Senior Circuit. Among them, and chosen for no particular reason, were Phil Linz (1966-1967), Phil Bradley (1988), and Phillippe Aumont (2012-2015). Dave Philley (1958-1960) was not especially great as a Phillie, but wins a special award for having the least distance between team and personal names.

A number of these Phils had Phillip as a middle name, but are nevertheless in the running. Chick Fullis, a centerfielder for the Phillies from 1933 to 1934, was actually named Charles Phillip Fullis. Jim Owens, who pitched for the Fightins from 1955 to 1962, was a Jim Phillip. Scott Phillip Aldred (1999-2000), Mark Phillip Brownson (2000) and “Dapper” Dan Phillip Howley (1913), all fit this bill. Some of these Phils were good (especially Owens), but none reached the lofty peak that might make them the Greatest Phil.

For reasons that can scarcely be fathomed, Phillip Walter Leinert, who debuted with the Phillies in 1919 and pitched for them through 1924, hid his Phil-ness behind the nickname of “Lefty”. The fates would punish him for his refusal to bear the standard of Phil by ensuring that another Phillie hurler would take the nickname and eclipse him with it. You can both take the honor of a nickname and still be a Phil. Just ask Phil Collins.

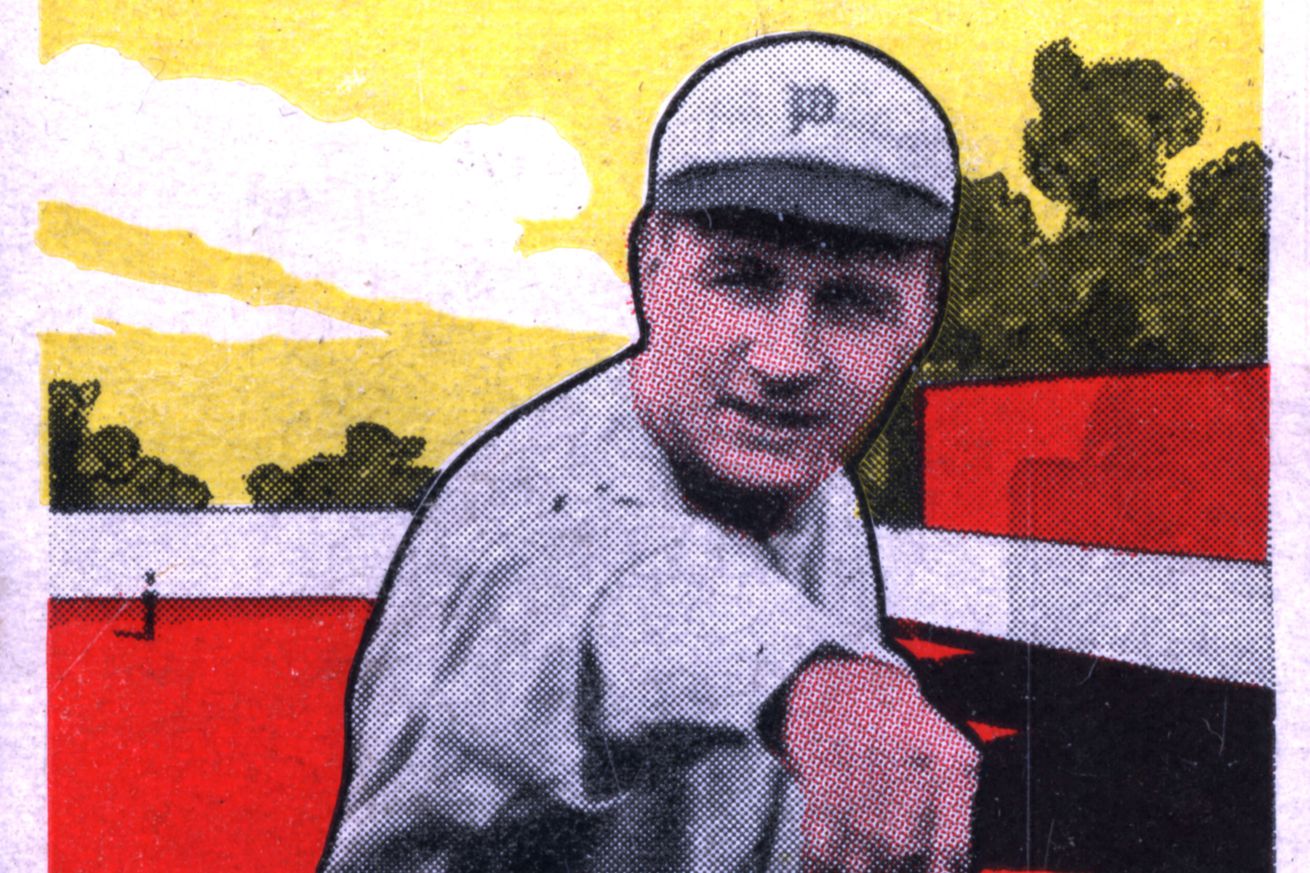

No, not that Phil Collins. Please put your Genesis records down (and onto the turntable, if you would; I rather like We Can’t Dance if you’ve got it). Instead, turn your attention to Phillip Eugene Collins, of Chicago. A righty pitcher, Collins made his major league debut in 1923 with his hometown Cubs, starting and winning a single game before disappearing back into the minors. That wasn’t even a sip of coffee. But six years later, he’d have the whole pot and more. He returned to major league ball at the age of 27 with the Phillies, for whom he would pitch six full seasons and part of a seventh. Along the way, he picked up the wonderfully alliterative nickname of Fidgety Phil.

In 1930, he put up a record of 16 wins and 11 losses, with an ERA of 4.78. He walked nearly as many as he struck out. But he pitched a whopping 239 innings, and threw 17 complete games, and came out of the bullpen on 22 occasions, and generally made himself useful to his club. As such, he accrued 5.3 wins above replacement that season. No Phil has ever accrued more WAR in a season played with the Phillies. Does that season make him one of the greats, either by league-wide or local standards? No. Does it make him particularly important in the lengthy history of the Philadelphia ball club? No.

But not every accomplishment in baseball has to be momentous. Baseball is full of trivia, and by the very naming we know that trivia is meant to be trivial. Fidgety Phil Collins is the Greatest Phil in Phillies history. Do with that what you will.

- No author given.“Phillies Whitewashed”. The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 12, 1891, pg 3.

- No title or author given. The Weekly Kansas Chief, July 30, 1891, pg. 2

- No author given. “6 Local attorneys at Saylor Funeral”. The Daily Advocate, July 27, 1937, pg. 1

Data on career statistics and games played via Baseball Reference.